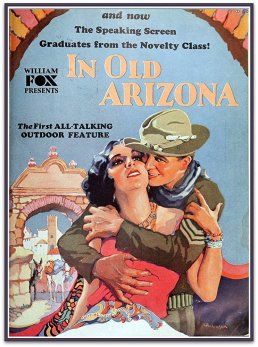

We shouldn’t celebrate the “first” of anything, really; we can celebrate the best of it, but the two are not necessarily equal. Groundbreaking technology or a story that has been told in a certain way for the first time is worth noting, but not celebrating. Insofar as humans are concerned with chronicling history, it matters that In Old Arizona was the first talking western, the first iteration of O. Henry’s “Calico Kid,” and the first instance of the singing cowboy motif so that we can compare any future iterations against these: we innovate because we don’t want to repeat the past.

We shouldn’t celebrate the “first” of anything, really; we can celebrate the best of it, but the two are not necessarily equal. Groundbreaking technology or a story that has been told in a certain way for the first time is worth noting, but not celebrating. Insofar as humans are concerned with chronicling history, it matters that In Old Arizona was the first talking western, the first iteration of O. Henry’s “Calico Kid,” and the first instance of the singing cowboy motif so that we can compare any future iterations against these: we innovate because we don’t want to repeat the past.

In all other instances, we can ignore innovation for the sake of progress. In Old Arizona is not a movie worth watching more than once, but it will remain on the List of Important Things forever.

That the film seems both longer and shorter that it is demands a deep dive into its editing. Sacrosanct firstness aside this movie is too long: the story is simple by design and follows an arc borne by stage and silent film – so why the 100 minutes? Director Irving Cummings and his editor, Louis Loeffler, must have thought that the valence of each scene maketh lean movie. Or, the financial reality left this team unable to make many cuts in post-production because refilming wasn’t an option. Or, actors’ contracts required a certain percentage of screen-time (or somewhat similar).

Or, and most likely, the editing techniques that audiences may know, but likely don’t see, were not yet developed yet. Loeffler relied too heavily on the cut-and-paste with room to insert dialogue cards used exclusively in silent film until that point. The hack job makes this film tiresome with what could have been a tight, 65 minute caper. This film speaks nothing necessarily of his ability as an editor, as he was nominated for Oscars over 30 years later for his work on 1960’s winner, The Apartment, and on The Cardinal.

Somewhere between 1928 and 1960, Louis Loeffler developed a keener eye and a better understanding of how to present raw film to an audience. It is, again, somewhat unfair to judge a pre-code, pro-talking film from the 1920s with much more than a firstness and newness lens. But there must have been an intertwining development of audience research, storytelling dynamism, and better technology to make the final cut of a film more entertaining for the sake of the story.

But wait: visionaries were already pushing boundaries of editing technique to tell a story. Sergei Eisenstein, director and editor of 1925’s seminal and essential Battleship Potemkin, had by this time developed and applied film-specific editing techniques that would later be collected into a general consensus for how to piece together narrative when all walls were fourth walls. Because the world, still very round at this time, had not yet caught up to him, In Old Arizona suffered from the disease of time and place. There cure, here, was time, technology, and a series of repetitive, dramatic mistakes to cut the difference between the two.

Had this movie been made 15 years later, however, would it have been any better? Americans had been fascinated with the built-in idea of Manifest Destiny and the West for decades until Clint Eastwood’s 1992 winner, Unforgiven, shut them down. By that point, had Eastwood have wanted to fly in a Russian editor, he could have. By that point, In Old Arizona would have lived up to its name.

The 2nd Academy Awards hosted, presumably, little fanfare. Another “first”: winner The Broadway Melody was the first “talking” musical and one of the first films to have filmed a scene in color (it has since been lost), but taking away the newness factor, the story seems somewhat vacuous, even by contemporary standards. Since DW Griffith and before, American filmmakers proved they could craft good stories. Unfortunately neither The Broadway Melody nor In Old Arizona was.

One thought on “[1928/29] In Old Arizona”