Some years ago, after the United States elected our dumbest citizen president, Aneela Mirchandani wrote for The Odd Post, “Twelve Angry Trump Voters,” casting each of Sidney Lumet’s fictional jurors as archetypical Trumpers, accompanied by quick but deft analysis as to why these jurors behaviors would translate into a Trump vote. With the exception of Juror no. 8, who Mirchandani astutely points out that his “not guilty” vote was not one of truth, but one of truth-seeking, the rest of the jurors are convinced of the prosecution’s case. This author makes a great case comparing attitudes from the foregone Great Era to today’s Great Again Era: they haven’t really changed. Maybe humans, as advanced apes and herd animals, are just wired this way.

Some years ago, after the United States elected our dumbest citizen president, Aneela Mirchandani wrote for The Odd Post, “Twelve Angry Trump Voters,” casting each of Sidney Lumet’s fictional jurors as archetypical Trumpers, accompanied by quick but deft analysis as to why these jurors behaviors would translate into a Trump vote. With the exception of Juror no. 8, who Mirchandani astutely points out that his “not guilty” vote was not one of truth, but one of truth-seeking, the rest of the jurors are convinced of the prosecution’s case. This author makes a great case comparing attitudes from the foregone Great Era to today’s Great Again Era: they haven’t really changed. Maybe humans, as advanced apes and herd animals, are just wired this way.

I first read Mirchandani’s essay at around the same time I discovered Dorothy Thompson’s essay, written for Harper’s in 1941, called “Who Goes Nazi?” In it, Thompson, who witnessed Hitler and Nazism’s rise in Germany in the 1930s, surveys a room of fictional soiree attendees, defining each by their nature and nurture and thusly assimilating them into two categories: would this person be a Nazi, or not? For it’s plaudits, “Who Goes Nazi?” is a blunt, sobering take and shouldn’t be taken as a syllogism: Nazism isn’t an “if this, then that.” It’s “if those, then him.” It’s a complicated business accusing fake people of being real Nazis.

It seems obvious in the age of obvious Trumpism (there’s always been threads of anti-intellectualism, but never as a hegemonic power) which of 12 Angry Men‘s jurors would have voted for 45, but the analysis is already done. Instead, it would be an interesting exercise to try and peg each character as one who would go Nazi, or not.

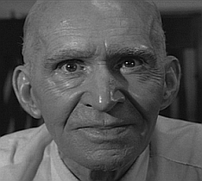

Martin Balsam as Juror 1, the jury foreman; an assistant high school American football coach. (not a Nazi)

Martin Balsam as Juror 1, the jury foreman; an assistant high school American football coach. (not a Nazi)

Juror 1 is not a Nazi. His neutrality is obvious and though he’d see the Nazis’ attempt to wrest control of the Reichstag and think nothing but politics-as-usual, until he’d begin to notice a growing number of small changes to his daily life. He’s interested in keeping the peace, and someone interested in the status quo doesn’t stir the pot, but nor does he actively oppose change. He’ll find his way to a country that is more liberated, perhaps the United States, before the first invasion. He’ll sign up to fight Nazis but will likely find a job pushing papers.

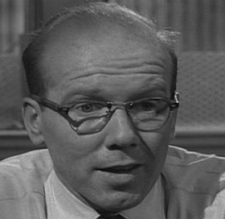

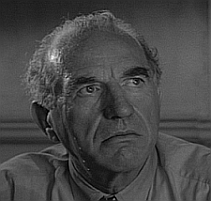

John Fiedler as Juror 2, a meek and unpretentious bank worker who is dominated by others. (Nazi)

John Fiedler as Juror 2, a meek and unpretentious bank worker who is dominated by others. (Nazi)

Besides Juror 10, Juror 2 is the most obvious Nazi of the bunch. He’ll be a rank-and-file Nazi, assigned to do unspeakable tragedy, and he’ll never find courage to say no to his superiors, of which there are many. After the war, he’ll plead ignorance and will be sentenced at Nuremburg.

Lee J. Cobb as Juror 3, a hot-tempered owner of a courier business who is estranged from his son; the most passionate advocate of a guilty verdict. (not a Nazi)

Lee J. Cobb as Juror 3, a hot-tempered owner of a courier business who is estranged from his son; the most passionate advocate of a guilty verdict. (not a Nazi)

Although the proclivity for Nazism is there, Juror 3 doesn’t feel hate towards everyone. He’s reeling from the relationship with his son and is projecting his feelings outward. He’s reasoned himself into his verdict, but is finally reasoned out after he’s forced to face his own feelings. Juror 3 could go Nazi, but only if he’s kept away from the true horrors, which would instantly flip him. Death couldn’t escape Germany in the 1930s; Juror 3 doesn’t go Nazi.

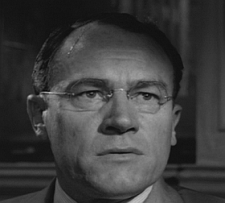

E. G. Marshall as Juror 4, a rational, unflappable, self-assured, and analytical stock broker. (Nazi)

E. G. Marshall as Juror 4, a rational, unflappable, self-assured, and analytical stock broker. (Nazi)

Juror 4 is the purest Nazi in the bunch; he’s found a way to rationalize National Socialism–not as a mechanism to scapegoat the other–but as a pathology toward net benefits to him and his family. He stands to gain by joining up with the Nazi party and would likely command others as his unflappable nature makes him perfect for this role. He’d likely have no problem subordinating Juror 10.

Jack Klugman as Juror 5, a man who grew up in a violent slum, sensitive to insults about his upbringing. (not a Nazi)

Jack Klugman as Juror 5, a man who grew up in a violent slum, sensitive to insults about his upbringing. (not a Nazi)

Juror 5 is proud of his heritage, and likely has spent time with people from all backgrounds. He’s continuously confused why others can’t follow his path out of poverty, and feels contempt toward those who try to cheat their way out. But he doesn’t feel right scapegoating them. He’s initially allured by the structure of Nazism but can’t stand for its ideals as, above all else, a hate group. Juror 5’s loyalty is to his community, and won’t stand for its people to be culled based on race or religion.

Edward Binns as Juror 6, a tough but principled house painter who consistently speaks up when others are verbally disrespected, especially the elderly. (not a Nazi)

Juror 6 might be persuaded to join the Nazi party when presented a compelling pro-German argument and is excited at the prospect of more work, but won’t ultimately join when he’s witness to unspeakable horrors in the name of the “German master race.” He holds respect for older members of his community and he won’t tolerate violence against them.

Jack Warden as Juror 7, a wisecracking salesman and Yankees fan who seems indifferent to his role. (Nazi)

Jack Warden as Juror 7, a wisecracking salesman and Yankees fan who seems indifferent to his role. (Nazi)

Juror 7 is mostly indifferent to the plight of the German people, but he does find humor in people disappearing around him. He’d certainly go Nazi, if only to “get on with it already.” He’d eventually be applauded for vocally opposing Jesse Owens’ success at the Olympics because those medals “are supposed to be ours.” Eventually he’d make the wrong joke to the wrong official and that will be the end of Juror 7.

Henry Fonda as Davis, Juror 8; an architect, initially the only one to vote “not guilty” and openly question the seemingly clear evidence presented. (not a Nazi)

Henry Fonda as Davis, Juror 8; an architect, initially the only one to vote “not guilty” and openly question the seemingly clear evidence presented. (not a Nazi)

Juror 8 would likely seek out Oskar Schindler, or another German defiant, and actively work against the Nazis out of deep principle and deep respect for humanity. He’d be among the first to recognize the power grab in 1932 and would be deep in secret meetings to overthrow the injustice. The Nazis would have a special reward for his capture.

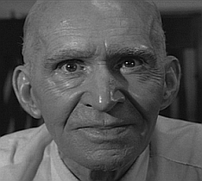

Joseph Sweeney as McArdle, Juror 9; an intelligent, wise, and observant senior. (not a Nazi)

Juror 9 would never be a Nazi, even if he’d agree to join the party. He doesn’t have the “qualities” needed to sustain the master race and would likely be instantly killed or dive deep into couter-insurgency with Juror 8.

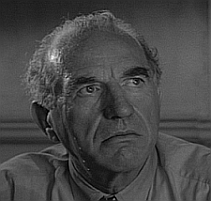

Ed Begley as Juror 10, a pushy, loud-mouthed, and bigoted garage owner. (Nazi)

Unlike Juror 3, Juror 10’s grievances are borne from a deep hatred of the “other,” likely taught to him by his parents or by his local news sources. He’d likely respond to shame if it was the dominant party’s position that his feelings were wrong. However, that’s not the case and his racial animus would like make Juror 10 easy to manipulate and placate with the explicit instructions to “remove” others that he deems “un-German” by the color of their skin or the difference of their beliefs.

George Voskovec as Juror 11, a European watchmaker and naturalized American citizen who demonstrates strong respect for democratic values such as due process. (not a Nazi)

George Voskovec as Juror 11, a European watchmaker and naturalized American citizen who demonstrates strong respect for democratic values such as due process. (not a Nazi)

Though naturalized, he’s as much American as his fellow jurors. Having witnessed the horrors of World War I, he’d never wish war on anyone, even if it means he stands the most to gain from a party that mostly aligns with his heritage. He’d never go Nazi, having spent so much of his life fighting against anti-democratic hatred in his home country.

Robert Webber as Juror 12, an indecisive advertising executive. (Nazi)

Robert Webber as Juror 12, an indecisive advertising executive. (Nazi)

Juror 12 would relish at the chance to sell any idea, as he was taught to do. He’d finally feel appreciated for his work, transforming his bland career into one more worthy of a cause célèbre–any cause célèbre–even if it means lots of his countrymen would be violently excluded. He would be convinced that he’s acting for the greater good and would be highly regarded among Nazi elite.

Of course this analysis is all fictional speculation and has no basis in reality. It’s a parlor game played to demonstrate character development. The very notion that all twelve jurors all have distinct enough personalities from a glorified table read to speculate their Nazism is a testament to the clarity of 12 Angry Men‘s script and Sidney Lumet’s deft direction.

The analysis could all be wrong, but that’s not the point. Humans are creatures of doubt and deserve to be judged on the soundness of their actions rather than on the whip of their wit. Watch what a man does when given ultimate power to choose. It’s this sense of wonder that sets 12 Angry Men apart. It’s hard to judge against Best Picture winner, The Bridge on the River Kwai. For its lasting power in 8th grade social studies classrooms, it should have been 12 Angry Men, though, and especially against Sayonara, Peyton Place, and an analogue, Witness for the Prosecution.

I sat down with

I sat down with  Unless it’s the editor’s intent, an audience shouldn’t notice cuts between shots or transitions between scenes. Think: the wipe edit in A New Hope; or, the match cut in 2001: A Space Odyssey; the dolly zoom interspersed with the violent action shots in

Unless it’s the editor’s intent, an audience shouldn’t notice cuts between shots or transitions between scenes. Think: the wipe edit in A New Hope; or, the match cut in 2001: A Space Odyssey; the dolly zoom interspersed with the violent action shots in  Despite Martin Scorsese’s best efforts to distinguish films from movies, studios still make low-brow, crowd-pleasers in bulk to help pay for the cinema Scorsese loves and makes. For every superhero reboot and sequel there’s a handful of arthouse dramas that will inevitably either be long, hooked foul balls or deep home runs. Cinephiles want as many of these made as possible, even if the majority of them are Green Book and not The Green Mile. We want creative chain lightning, but we’ll take the trash heap too. I take Scorsese at his word. He’s certainly earned the right to be cranky in public without reproach.

Despite Martin Scorsese’s best efforts to distinguish films from movies, studios still make low-brow, crowd-pleasers in bulk to help pay for the cinema Scorsese loves and makes. For every superhero reboot and sequel there’s a handful of arthouse dramas that will inevitably either be long, hooked foul balls or deep home runs. Cinephiles want as many of these made as possible, even if the majority of them are Green Book and not The Green Mile. We want creative chain lightning, but we’ll take the trash heap too. I take Scorsese at his word. He’s certainly earned the right to be cranky in public without reproach. “What’s in a name?”

“What’s in a name?” Some years ago, after the United States elected our dumbest citizen president, Aneela Mirchandani wrote for

Some years ago, after the United States elected our dumbest citizen president, Aneela Mirchandani wrote for  Martin Balsam

Martin Balsam John Fiedler

John Fiedler

Jack Klugman

Jack Klugman

Jack Warden

Jack Warden

George Voskovec

George Voskovec Robert Webber

Robert Webber