The true horror of the sprint towards my own death has not yet set in. I still feel I am jogging through the spring of my own life and refer to those older than me as that – older. Maybe wiser and certainly more cynical (cynicism for cynicism’s sake, it seems), but older. Perhaps I live an insulated life, balancing school with my desire to do nothing. It creeps along.

The true horror of the sprint towards my own death has not yet set in. I still feel I am jogging through the spring of my own life and refer to those older than me as that – older. Maybe wiser and certainly more cynical (cynicism for cynicism’s sake, it seems), but older. Perhaps I live an insulated life, balancing school with my desire to do nothing. It creeps along.

But I do have friends and even when I don’t see my friends for long periods of time, when we do meet, it’s as though nothing has changed. We’re older, collectively, and we no longer complain about the same things, but we have each other and we have our stories to find comfort in them. Since we’ve left each other’s daily company, we’ve had time to breathe, and while we don’t share the same experiences, we experience together. The dynamic seems to be cyclical in that we continue to learn from one another’s separate experiences. Though separated by 200 miles, we have phones, email, social media and any other way to replicate the experience of being together. It doesn’t take an event to get us together. The Big Chill replicates 70% of my experience. Continue reading

This post will be in two parts within this block of text. I’ve decided to undergo a thought exercise: what can I parse about this movie based on the title? How right/wrong will I be after I watch it? What does it mean if I can or cannot guess at certain plot points before the fact? Does predictability mean anything?

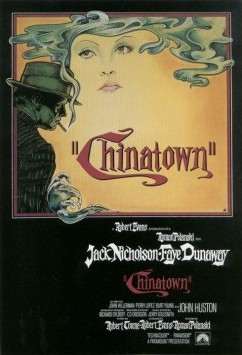

This post will be in two parts within this block of text. I’ve decided to undergo a thought exercise: what can I parse about this movie based on the title? How right/wrong will I be after I watch it? What does it mean if I can or cannot guess at certain plot points before the fact? Does predictability mean anything? I broke my own rule on this one because I’d seen this film a few times before. But they’re my “rules” and, truthfully, it doesn’t matter, because I was interested in taking this film on as a corollary to my education as an urban planner. A professor of mine had mentioned in passing that Chinatown was the best “planning” movie ever made. If I can extrapolate a little further, what Professor Landis meant was more along the lines of “Chinatown is the best movie ever made in an urban setting whose main plot piece revolves around zoning and water/land use,” two issues dear to every urbanist’s heart. To the passing urbanist – an effete young worker in a sea of tall buildings and traffic congestion – issues of environmental justice and invisible infrastructure mean very little, yet are continuously essential to the maintenance of a thriving city. Most movies assume the standardization of the proxy: by translating the image of what the reader knows to frame the story onto the screen, there exists no need to redefine the space. This is the very fact upon which “dystopian” story exploits. Chinatown is not set in a dystopia – in fact the very opposite.

I broke my own rule on this one because I’d seen this film a few times before. But they’re my “rules” and, truthfully, it doesn’t matter, because I was interested in taking this film on as a corollary to my education as an urban planner. A professor of mine had mentioned in passing that Chinatown was the best “planning” movie ever made. If I can extrapolate a little further, what Professor Landis meant was more along the lines of “Chinatown is the best movie ever made in an urban setting whose main plot piece revolves around zoning and water/land use,” two issues dear to every urbanist’s heart. To the passing urbanist – an effete young worker in a sea of tall buildings and traffic congestion – issues of environmental justice and invisible infrastructure mean very little, yet are continuously essential to the maintenance of a thriving city. Most movies assume the standardization of the proxy: by translating the image of what the reader knows to frame the story onto the screen, there exists no need to redefine the space. This is the very fact upon which “dystopian” story exploits. Chinatown is not set in a dystopia – in fact the very opposite. Raise your hand if you’ve heard or seen the following framework before, then after you’re done put your hand down if you’re under the age of eighty:

Raise your hand if you’ve heard or seen the following framework before, then after you’re done put your hand down if you’re under the age of eighty: Hey loyal reader(s)! Back after a long hiatus – school beckons. I’ve got some free time now and I’ll try to post 2-3 a week. Let’s start with 2014’s Boyhood, a movie some consider “runner-up” to 2014’s eventual winner Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance). I’ve had a fair few conversations where the main point of contention was anything less than a win for Boyhood would be (before the Awards) or was (after) a direct insult to the novelty of longitudinal film making. That said, it is a good exercise to begin to understand the cagey genius of Boyhood. Although an entertaining film to say the least, levels of inauthenticity continue to plague how I remember the film.

Hey loyal reader(s)! Back after a long hiatus – school beckons. I’ve got some free time now and I’ll try to post 2-3 a week. Let’s start with 2014’s Boyhood, a movie some consider “runner-up” to 2014’s eventual winner Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance). I’ve had a fair few conversations where the main point of contention was anything less than a win for Boyhood would be (before the Awards) or was (after) a direct insult to the novelty of longitudinal film making. That said, it is a good exercise to begin to understand the cagey genius of Boyhood. Although an entertaining film to say the least, levels of inauthenticity continue to plague how I remember the film.