Sometimes a song is just meant for the screen. Even without any visuals to accompany it, it’s cinematic on its own; it tells a story, conveys a meaning, and conjures a time and place. “That’s Amore” by Dean Martin was born for film, quite literally, in that it was commissioned specifically to be performed by Martin in 1953’s The Caddy, but it’s somehow more at home when soundtracking a montage of people on dates eating pasta. It almost does a filmmaker’s work for them, as when director Norman Jewison pairs it with glittering imagery of Brooklyn Heights and the Metropolitan Opera House in the opening sequence of Moonstruck. The audience knows exactly what will happen next: high passions, red wine, and Italian accents.

Few songs have had the reach “That’s Amore” has commanded over the decades, and despite its overtness and obviousness, we still associate it with success and accolades. It garnered an Academy Awards nomination for Best Original Song upon its debut in The Caddy, losing to “Secret Love” from Calamity Jane as one might expect: serious fare often earns more respect than lighter material. Later, “That’s Amore” set the stage for Cher, Olympia Dukakis, and writer John Patrick Shanley to all win their sole Oscar awards. At a time when the movie-going public was buying up tickets to action movies and thrillers, the Academy slowed down, took a breath, and recognized the ambitious acting and crystal-clear characterization the cast of Moonstruck was able to deliver. In 1987, “That’s Amore” primed audiences for a comedically fraught romance with bombastic performances that mix Old World realism with stereotypes informed by the observational eye of a playwright, and they were ecstatic when that’s what they got.

Only a year after the debut of “That’s Amore,” Alfred Hitchcock borrowed it to great and jarring effect in Rear Window (also nominated for awards from the Academy). The song already had such immediacy and cultural weight that The Master of Suspense was able to subvert its romantic message by removing the lyrics and using it to score a scene where a man spies on a newlywed couple from his window through theirs. It’s impossible to avoid mentally singing the lyrics to yourself, crossing the signals in your brain between the romantic and the voyeuristic. You know intellectually that the newlyweds are in the throes of love like the song describes, but you’re not with them: you’re with the peeping tom. Hitchcock relied on the original music’s instant popularity and inherent romantic meaning to create an uncomfortable dissonance for his viewers to sit with. Continue reading

Here is a short rundown of

Here is a short rundown of

The Gilded Age in the American experience subsists as worthwhile to study because of its uninterrupted, demonstrated prosperity (curiously corresponding to a legal ban on drink) immediately followed by superficially mitigated disaster and calamity. The Depression certainly carved space for the creation of great works; jazz and photography each had hallmark decades and increased the breadth and depth of its craft. Advances in telecommunications, regardless of who could afford them, allowed for this art to democratize and to offer at least a distraction and at most a joy to millions of people who had nothing now but drink and unsalable assets. Authors who write about this transitory time ex post facto get the benefit of knowing in advance what came next. What makes The Great Gatsby brilliant makes its later Contemporary American Novels not so much: perspective, of which we know Scott Fitzgerald had little.

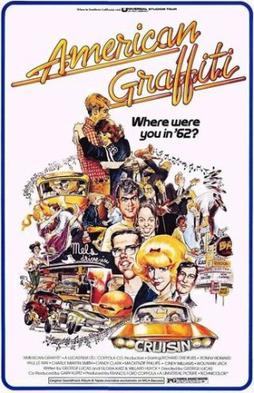

The Gilded Age in the American experience subsists as worthwhile to study because of its uninterrupted, demonstrated prosperity (curiously corresponding to a legal ban on drink) immediately followed by superficially mitigated disaster and calamity. The Depression certainly carved space for the creation of great works; jazz and photography each had hallmark decades and increased the breadth and depth of its craft. Advances in telecommunications, regardless of who could afford them, allowed for this art to democratize and to offer at least a distraction and at most a joy to millions of people who had nothing now but drink and unsalable assets. Authors who write about this transitory time ex post facto get the benefit of knowing in advance what came next. What makes The Great Gatsby brilliant makes its later Contemporary American Novels not so much: perspective, of which we know Scott Fitzgerald had little. Nostalgia is a hell of a marketing technique. It, as a concept, can be sufficiently disaggregated so that each person’s experience is both universal and personal. Lots of new media relies on the unreachable past. There exists, as I’ve written about before, a term called sonder, which means nostalgia for a time not one’s own. Midnight in Paris captures this feeling to the letter, and commodifies it so that its message can be bought and sold by the very people it aims to placate with dreams of subservience to the artistes de La Belle Époque. Nostalgia is also overwhelming. Instead of inspiration, nostalgic media inspires selective memory, further confusing past narratives. Drowning in nostalgia is akin to a drug-induced coma. Here’s the trick for those who insist on capitalizing on it: rinse and repeat. People will become nostalgic of their own nostalgia.

Nostalgia is a hell of a marketing technique. It, as a concept, can be sufficiently disaggregated so that each person’s experience is both universal and personal. Lots of new media relies on the unreachable past. There exists, as I’ve written about before, a term called sonder, which means nostalgia for a time not one’s own. Midnight in Paris captures this feeling to the letter, and commodifies it so that its message can be bought and sold by the very people it aims to placate with dreams of subservience to the artistes de La Belle Époque. Nostalgia is also overwhelming. Instead of inspiration, nostalgic media inspires selective memory, further confusing past narratives. Drowning in nostalgia is akin to a drug-induced coma. Here’s the trick for those who insist on capitalizing on it: rinse and repeat. People will become nostalgic of their own nostalgia. Power can be a frightening subject, but it can also be used to explain away the end of things. Partnerships, whether thrust upon or voluntary, are continuous, minor exchanges of power throughout. When a sovereign directs his subjects to do the bidding of the Crown, the King is exploiting his uninundated power upon ultimately powerless people. When democratic processes mask power, through funnymoney campaigns, who wins? Power can always be recast as a struggle among constituencies; always in motion, teetering atop a spinning point. At some point, every aspect breaks, in order, without notices. Nothing knows existence anymore.

Power can be a frightening subject, but it can also be used to explain away the end of things. Partnerships, whether thrust upon or voluntary, are continuous, minor exchanges of power throughout. When a sovereign directs his subjects to do the bidding of the Crown, the King is exploiting his uninundated power upon ultimately powerless people. When democratic processes mask power, through funnymoney campaigns, who wins? Power can always be recast as a struggle among constituencies; always in motion, teetering atop a spinning point. At some point, every aspect breaks, in order, without notices. Nothing knows existence anymore. The Western ceased as an artform in early 1993, when Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven closed the chapter on a much-loved and rarely-maligned genre. Westerns were wholly post Manifest United States, though their premise has been recycled through Shakespeare and Kurosawa, setting the human experience against a backdrop of nothhingness – as the desert has sand and more desert – removes the setting from the movie’s intent. Every character written into a western usually exudes an invisible two-mile sphere from her center point that seemingly bounces off every object with which it comes in contact. This is a prerequisite for this genre it seems, that operates on lone-wolf syndrome and synthesis: the character on which we focus has a larger bubble than everyone else and we, the audience, are supposed to fit empathy inside of it.

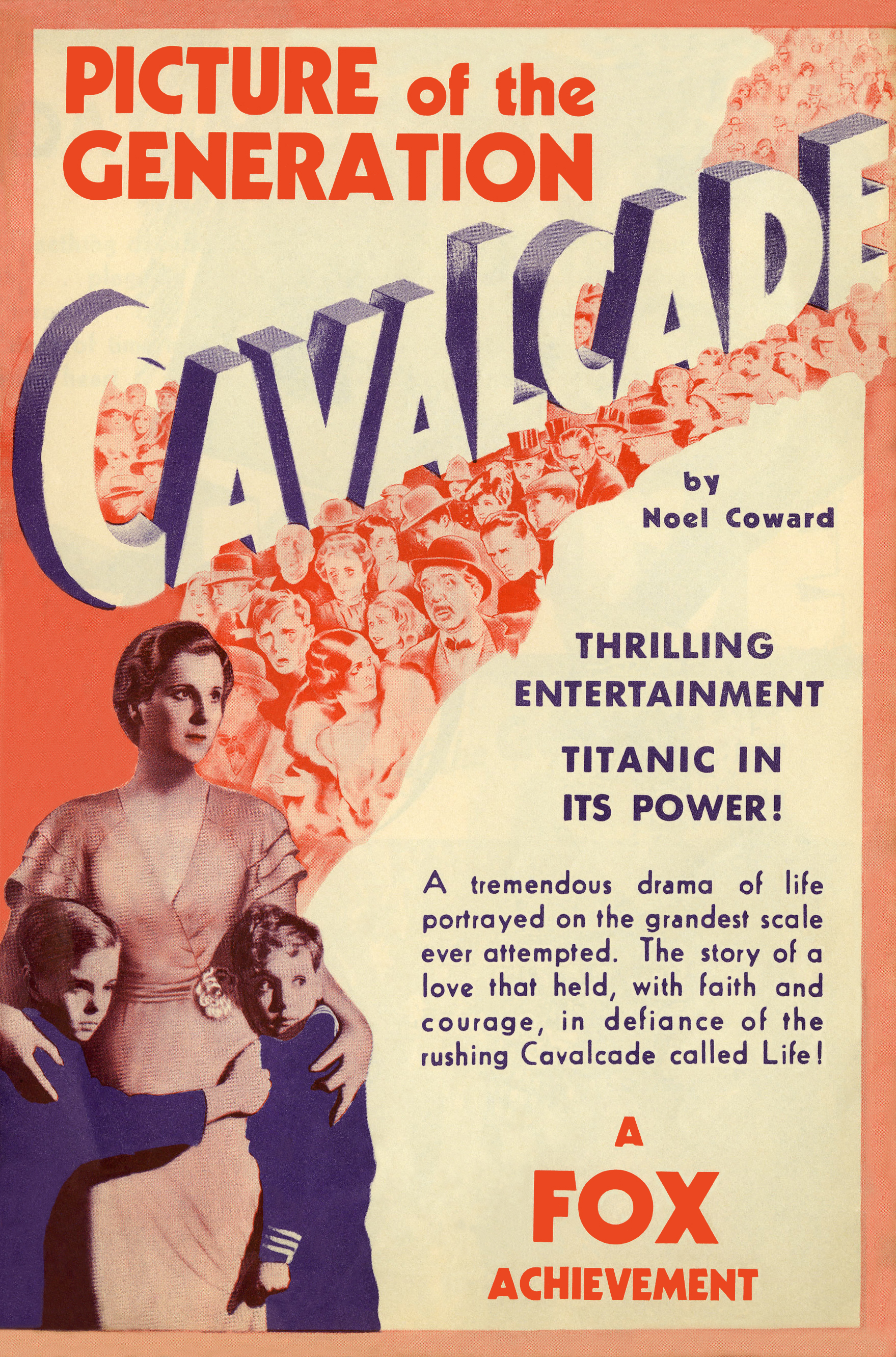

The Western ceased as an artform in early 1993, when Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven closed the chapter on a much-loved and rarely-maligned genre. Westerns were wholly post Manifest United States, though their premise has been recycled through Shakespeare and Kurosawa, setting the human experience against a backdrop of nothhingness – as the desert has sand and more desert – removes the setting from the movie’s intent. Every character written into a western usually exudes an invisible two-mile sphere from her center point that seemingly bounces off every object with which it comes in contact. This is a prerequisite for this genre it seems, that operates on lone-wolf syndrome and synthesis: the character on which we focus has a larger bubble than everyone else and we, the audience, are supposed to fit empathy inside of it. A type of visceral film exists that is aware of its own structure. Cavalcade is one of them, it might be the first one, and it won Best Picture at the 3rd Academy Awards. The voters probably noticed it and wished to confer upon it a nod of appreciation for a book like handling of a character driven slice-of-life drama. It isn’t even an odd choice, considering talking film was still forming as a process, that a film that took advantage of large sets and big, blocky characters would win an honor that meant, probably, technical achievement in filmmaking as much as it did representation of the human experience. Curiously, on its face, Cavalcade is not particularly interesting: a well-to-do English family faces minor inconveniences among a host of relative stability; their staff, seemingly content but hungry to join an upper echelon, is a normal view on the human experience from a Depression vantage point. It probably projects a more modern experience onto a proto-Victorian, fin de siècle experience than was likely. This movie approaches class almost apathetically, vacating all pretense when the plot simply moves along among tragedy. This approach flattens the movie and rips from it the ability for a modern audience to appreciate its candor and stiff-upper-lip mentality. Cavalcade is quintessentially British, Depression-era, and pre-code. It is also lightly meta.

A type of visceral film exists that is aware of its own structure. Cavalcade is one of them, it might be the first one, and it won Best Picture at the 3rd Academy Awards. The voters probably noticed it and wished to confer upon it a nod of appreciation for a book like handling of a character driven slice-of-life drama. It isn’t even an odd choice, considering talking film was still forming as a process, that a film that took advantage of large sets and big, blocky characters would win an honor that meant, probably, technical achievement in filmmaking as much as it did representation of the human experience. Curiously, on its face, Cavalcade is not particularly interesting: a well-to-do English family faces minor inconveniences among a host of relative stability; their staff, seemingly content but hungry to join an upper echelon, is a normal view on the human experience from a Depression vantage point. It probably projects a more modern experience onto a proto-Victorian, fin de siècle experience than was likely. This movie approaches class almost apathetically, vacating all pretense when the plot simply moves along among tragedy. This approach flattens the movie and rips from it the ability for a modern audience to appreciate its candor and stiff-upper-lip mentality. Cavalcade is quintessentially British, Depression-era, and pre-code. It is also lightly meta. Movies like War Horse are terribly misleading. Movies like War Horse sell the audience on emotional resonance through distance and time: that any situation can be made good if we just throw enough stimuli at it. Not only is this misleading, it’s dishonest, and if our goal is to make a movie fun, then producers of movies like War Horse certainly think lying is the most fun. We can pass on this movie as a piece of serious art and a piece of frivolous fun, mostly because it’s almost three hours long and the main point seems to be “this horse can survive through WAR, what are you doing with your life?”

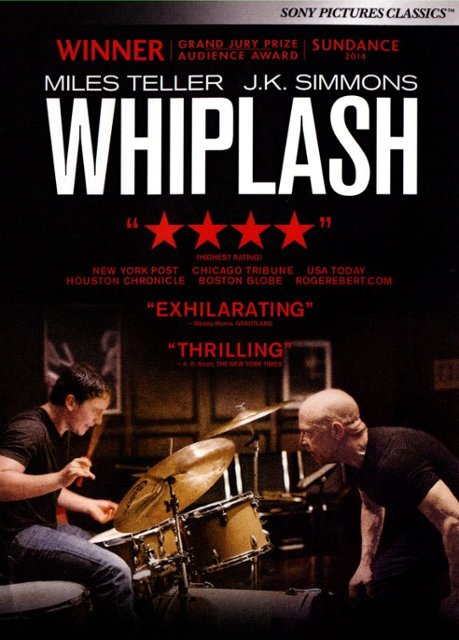

Movies like War Horse are terribly misleading. Movies like War Horse sell the audience on emotional resonance through distance and time: that any situation can be made good if we just throw enough stimuli at it. Not only is this misleading, it’s dishonest, and if our goal is to make a movie fun, then producers of movies like War Horse certainly think lying is the most fun. We can pass on this movie as a piece of serious art and a piece of frivolous fun, mostly because it’s almost three hours long and the main point seems to be “this horse can survive through WAR, what are you doing with your life?” Mediocre acting performances treated as legendary run rampant throughout film history. It adds to a film’s mystique when a consensus concerned critique deems a performance more than merely marginal — it elevates the lore to must-see status for film novices, and will often be included on best-of lists by more seasoned viewers. Reputation begins to precede its merits and once a film reaches this status, merited or not, subjective review loses meaning. It becomes too popular to deride for fear of contrarianism.

Mediocre acting performances treated as legendary run rampant throughout film history. It adds to a film’s mystique when a consensus concerned critique deems a performance more than merely marginal — it elevates the lore to must-see status for film novices, and will often be included on best-of lists by more seasoned viewers. Reputation begins to precede its merits and once a film reaches this status, merited or not, subjective review loses meaning. It becomes too popular to deride for fear of contrarianism.